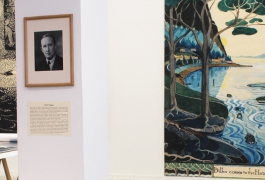

Tolkien the illustrator

By Jean-François Luneau, lecturer and researcher in the History of Art at the University of Clermot-Auvergne in France.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892-1973) is not only the author we all know, but he was also a talented illustrator. Many of his writings published when he was alive are accompanied by his illustrations.

As of 1920, Tolkien got into the habit of sending his children a letter signed by Father Christmas himself every year. These letters were accompanied by one or more wonderfully detailed illustrations that depicted the story told by Father Christmas. In 1926, he illustrated the Northern lights in the Land of Father Christmas. Two years later, he depicted a Clumsy Polar Bear helping Father Christmas prepare the Presents. In 1933, he wrote and illustrated the story telling of Father Christmas quietly sleeping in his newly decorated bedroom, while his loyal polar bear, helped by red elves, chased the goblins who invaded the cave where the presents were being prepared..

This child-friendly art is obviously not the most famous of Tolkien’s works: we are more familiar with his stories set in Middle-earth. Drawing on the influence of epic poems from Anglo-Saxon literature (such as Beowulf), the Icelandic or Norwegian Sagas, the Icelandic Eddas collection, the Finnish Kalevala or certain William Morris novels, Tolkien creates a fantasy world within the fertile setting of Middle-earth, which recalls the fertile setting of Brittany.

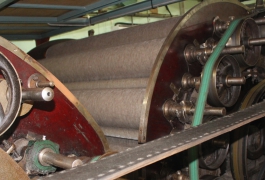

It is here, in this setting, teeming with figures and myths, that Tolkien brings his characters to life. In the same way that you pull on a yarn of wool to undo the ball, Tolkien unravels their stories, even if it means returning to the initial skein and adding to it to tie it in with the great finished novels such as The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings.

Several of Tolkien’s illustrations accompany the birth and growth of Middle-earth, depicting its geographical originality. The works that refer to different episodes are also a pretext for presenting the landscapes. The Halls of Manwë on the Mountains of the World above Faërie, drawn in 1928, represents Taniquetil, the High Shining White Peak dominating the Pelóri mountains, those towering mountainous defences that protect the Eastern borders of Valinor, country of the Valar. The mansion of the first Valar, Manwë, is perched on its summit where he reigns with his wife, Varda. The Taniquetil is certainly one of those ‘mountains seen far away, never to be climbed’ that Tolkien evokes in one of the letters to his son Christopher (Letter 96).

Beleriand, on the Western edge of Middle-earth, is where the events of the First Age take place. Lake Mithrim is situated in North Beleriand, in Hithlum. It is here, on the shores of the lake, that Fëanor wins the second battle against the armies of Morgoth, also called the Battle under the Stars. Glaurung sets forth to seek Túrin is one of the final episodes of The Lay of the Children of Húrin, written between 1918 and 1925, which ends in the death of the dragon Glaurung and the suicide of Túrin. This first dragon created by Morgoth, a fallen Valar, is as feared for the fire he breathes as for the bewitching words he speaks and his hypnotic lidless eyes.

Beleriand disappears at the end of the First Age, submerged after the fall of Morgoth and the ensuing cataclysm. The fate of Númenor Island, on the west side of the World, between Valinor and Middle-earth, is no better. It is a kingdom founded by men that sinks into the sea at the end of the Second Age. In the Third Age, its past splendour is but a memory, just like the Númenorian Carpet, where the geometrical perfection of the shape reflects the kingdom at its birth.

Tolkien provided illustrations for The Hobbit, a novel published in 1937, from the very first editions. Sometimes the drawings were in black and white, like The Trolls, whose air of stupidity disappears against a dark forest background magnified by the monochrome effect. As with some of the works mentioned above, the human characters often blend into a spectacular landscape. Rivendell and its Last Homely House evokes the scenery of the Swiss Alps. In Bilbo Woke Up with the Early Sun in His Eyes and Bilbo comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves, the majesty of the landscapes eclipses the figures of Bilbo asleep, or of the dwarves as burlesque victors perched on barrels. Lastly, in Conversation with Smaug, a dragon with a keen sense of smell and as talkative as he is dangerous, Tolkien chose the moment when Bilbo greets him: ‘Oh Smaug the Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities’.

In The Lord of the Rings, an epic novel that follows on from The Hobbit and was published in 1954-55, Tolkien explains why the elves left Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age. The Forest of Lothlórien in Spring illustrates the ‘land of Lórien’, where in Frodo’s eyes, ‘there was no stain’: a forest outside of space and time, and populated with mallorns, those trees with golden leaves.

As for The Tower of Orthanc rising at the centre of the Ring of Isengard, a region offered for safe-keeping to Saruman by the steward of Gondor, the illustration by Tolkien may actually be less scary than the text itself.

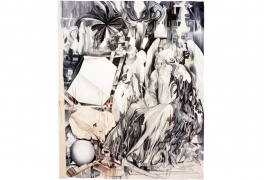

Tolkien’s rich Middle-earth setting provided him with the substance to weave long narratives and create several texts – a name also given to fabrics according to a multimillenial metaphor. And now, Tolkien’s illustrations will be woven into a tapestry wall-hanging. Whether they be epic or comic in nature, or just simple landscapes, Tolkien’s illustrations are ideal for being transposed into tapestry. As we cannot visit the palace of Théoden in Edoras, whose walls are adorned with tapestries narrating the deeds of the ancestor of the Rohan knights, Eorl the Young, we can at least admire the woven memory of Tolkien’s fantasy world.